Input vs Output Voltage: Cable Effects, Drops, and Fixes

Input vs Output Voltage: what changes once a cable is involved

In real systems, input vs output voltage is rarely identical when power travels through a cable. The difference is usually caused by voltage drop across the cable’s resistance and connectors. If the load draws current, even a “good” cable will produce a measurable drop, which can lead to dim LEDs, unstable DC motors, device resets, or failed charging.

A practical way to think about it:

- Input voltage: the voltage at the source side (power supply terminals).

- Output voltage: the voltage at the load side after the cable and connectors.

- Difference: mostly cable/connector drop that increases with current, length, and smaller conductor size.

When troubleshooting, measure at both ends. A supply can be “perfect” at its output terminals while the device sees a much lower voltage at the end of a long or thin cable.

The core equation: cable voltage drop in one line

For DC (and for the resistive portion of AC), the working approximation is:

Vdrop = I × Rtotal

Where Rtotal includes both conductors (outgoing + return) plus connector/contact resistance. For a two-wire cable, the “round-trip” length is twice the one-way length. If you know the cable’s resistance per meter (or per foot) you can estimate:

- Round-trip length = 2 × one-way length

- Rtotal ≈ (resistance per length) × (round-trip length) + connector resistance

Then output voltage is simply:

Vout = Vin − Vdrop

Real examples: how a cable creates input vs output voltage gaps

Example A: 12V device, long run, moderate current

Suppose you have a 12V supply and a device drawing 5A. The cable is 10 m one-way (20 m round-trip). If the cable’s round-trip resistance works out to 0.20 Ω, then:

- Vdrop = 5 A × 0.20 Ω = 1.0 V

- Vout = 12 V − 1.0 V = 11.0 V

This is often acceptable for motors and some LEDs, but it can be a problem for electronics that require a tight tolerance.

Example B: 5V device, same drop, bigger consequence

If a 5V device sees a 1.0 V drop, Vout becomes 4.0 V. That is a 20% reduction—often enough to cause USB-powered devices to disconnect or microcontrollers to brown out. The key insight is that lower-voltage systems are usually more sensitive to cable drops.

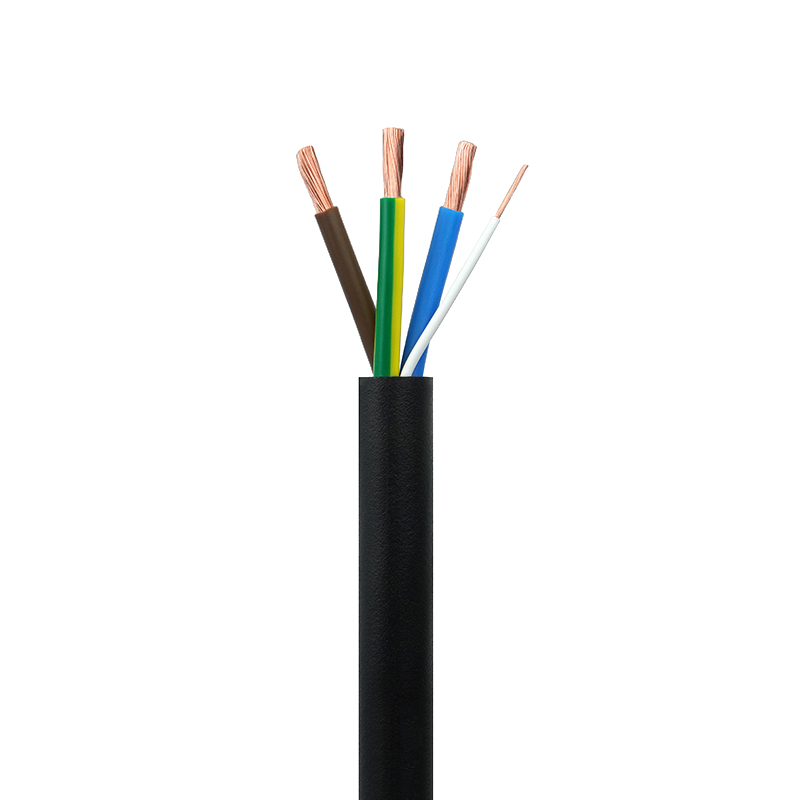

Cable factors that most strongly affect output voltage

Length: drop scales linearly

If you double the one-way cable length, you double the round-trip resistance and approximately double the voltage drop at the same current. Long runs are the fastest way to create a noticeable input vs output voltage difference.

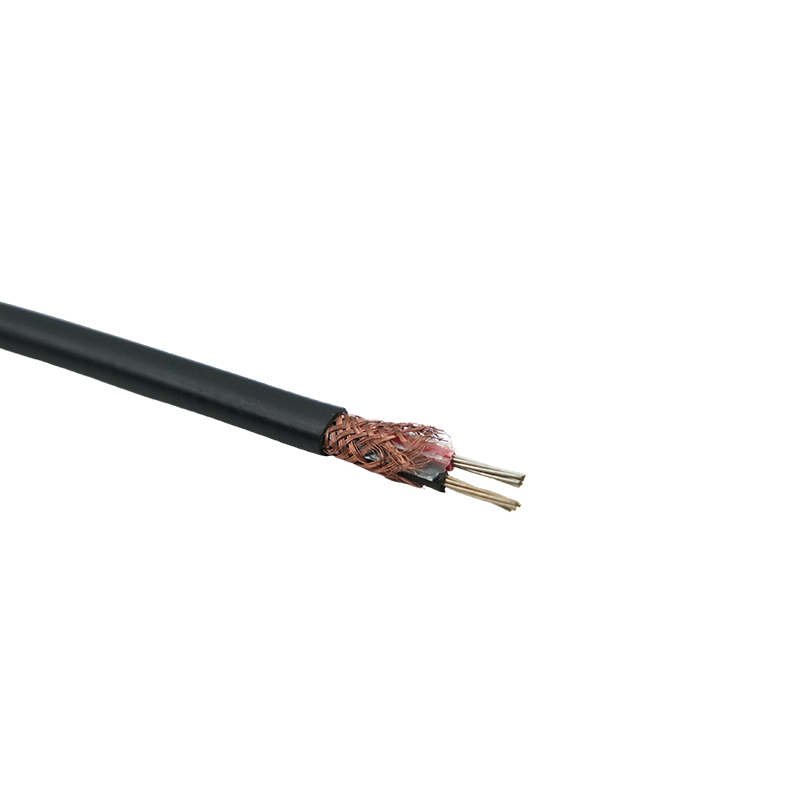

Conductor size: thinner wire increases resistance

Smaller-gauge (thinner) conductors have higher resistance per meter. This makes the output voltage sag more under load. If a device works on a short cable but fails on a longer one, wire gauge is a prime suspect.

Current: drop rises with load demand

Current is the multiplier in Vdrop = I × R. A system that draws 2A can tolerate cable resistance that would be disastrous at 10A.

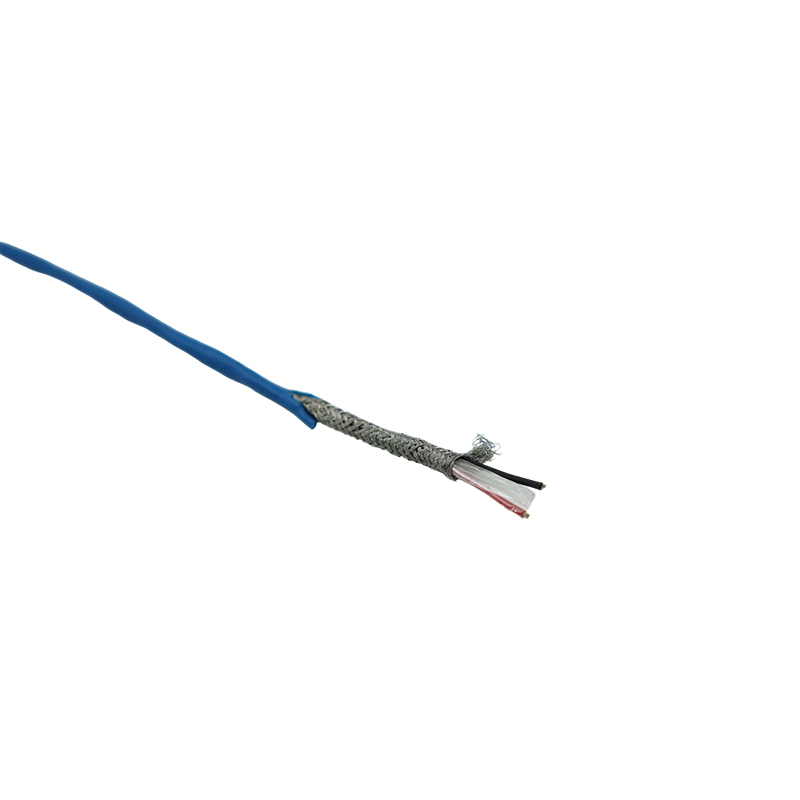

Connectors and contacts: small parts, big impact

Loose connectors, undersized crimp terminals, and corroded contacts add resistance and can create a disproportionate drop—especially at higher currents. In practice, a poor connector can contribute as much drop as several meters of cable. If the connection feels warm, treat it as a critical warning sign.

Quick planning table: acceptable voltage drop targets

| System type | Suggested max drop | Practical reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| 5V logic / USB-powered electronics | 2%–5% (0.10–0.25V) | Small absolute drops can cause resets and disconnects. |

| 12V lighting, fans, general loads | 3%–8% (0.36–0.96V) | Many loads tolerate moderate sag without malfunction. |

| 24V industrial control / actuators | 3%–5% (0.72–1.20V) | Controls prefer stable voltage; 24V helps reduce current. |

| Battery-to-inverter / high current DC | 1%–3% | High currents make small resistances costly and hot. |

If you do not have a formal spec, a practical rule is to design for ≤5% drop in most low-voltage DC applications, and tighten that to ≤3% for sensitive electronics.

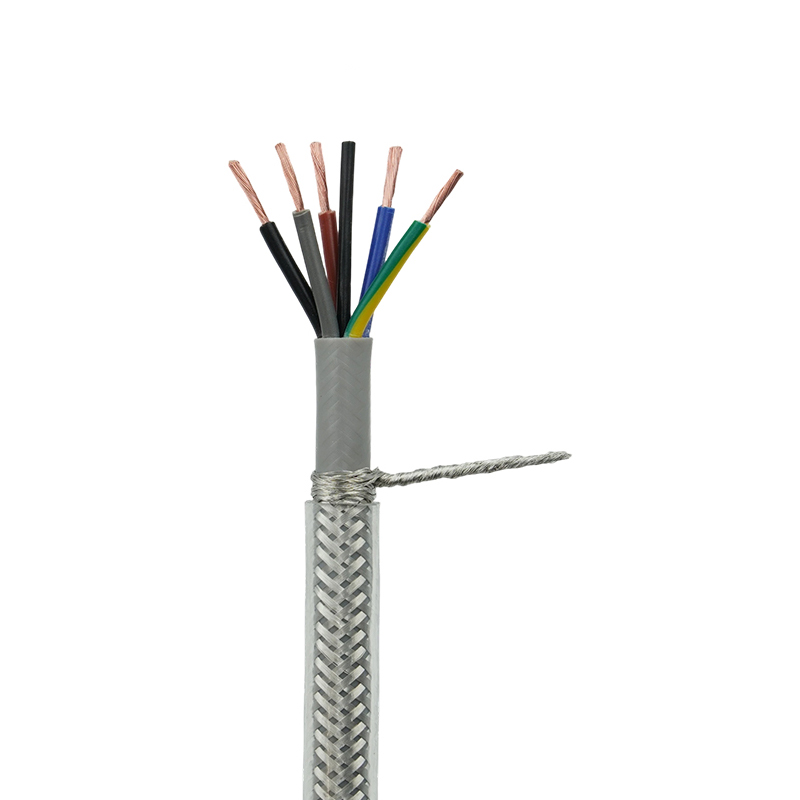

How to choose a cable to protect output voltage

Step 1: define current and allowable drop

Identify the worst-case load current (not the average), then decide the maximum voltage drop you can tolerate at the load. For example, if Vin is 12V and you allow 0.6V drop, your target is 5%.

Step 2: compute the maximum cable resistance

Rearrange Vdrop = I × R:

Rmax = Vdrop / I

If you allow 0.6V drop at 5A, then Rmax = 0.6 / 5 = 0.12 Ω total (round-trip plus connectors). Compare that to the cable’s resistance over your run length to choose an appropriate conductor size.

Step 3: account for connectors and temperature

Connectors add resistance and can worsen over time. Also, copper resistance increases with heat, meaning a cable carrying high current in a warm environment can drop more than expected. For reliability, treat your calculated result as a minimum and select the next heavier cable size when feasible.

Fixes when output voltage is too low at the end of the cable

Use a thicker or shorter cable

Reducing cable resistance is the most direct solution. A shorter run and/or larger conductor cross-section reduces Vdrop immediately.

Raise distribution voltage, then regulate near the load

If the load power is fixed, using a higher distribution voltage reduces current (P = V × I), which reduces drop. A common approach is to distribute at 12V or 24V, then use a DC-DC converter near the device to produce 5V. The key advantage is that lower current means proportionally lower cable losses.

Improve connectors and terminations

Re-terminate crimps, clean contacts, and use connectors rated for the current. If a connector is undersized, it can create localized heating and additional drop. For high-current paths, prefer robust screw terminals, quality crimp lugs, or purpose-built power connectors.

Measure drop under load, not at idle

A no-load measurement can be misleading because I is near zero, making Vdrop near zero. To confirm the true input vs output voltage, test while the load draws its typical or peak current.

A practical checklist for diagnosing input vs output voltage problems

- Measure Vin at the supply terminals and Vout at the load terminals while operating normally.

- If the difference exceeds your target (often ≤5%), shorten the run or increase conductor size.

- Inspect connectors for looseness, discoloration, or heat; fix terminations before changing the supply.

- If the system is low-voltage/high-current, consider distributing at a higher voltage and regulating locally.

- Re-check after changes and document the final measured input vs output voltage for future maintenance.

When managed intentionally, cable selection and layout can keep output voltage close to input voltage, improving stability and preventing intermittent faults that are otherwise hard to reproduce.

EN

EN

English

English русский

русский Español

Español