Voltage vs Ampere: What They Mean and How to Use Them Safely

Voltage vs ampere: the direct answer

Voltage (V) is the electrical “push” and ampere/current (A) is the electrical “flow.” In practical terms: voltage tells you what a device needs to operate, while amperes tell you how much current it will draw at that voltage. The two are linked by power: P (watts) = V × A.

This is why “higher voltage” does not automatically mean “more dangerous current,” and why “higher amperes” on a power supply is often fine: current is largely determined by the load, as long as the voltage is correct and the supply can provide enough amperes.

What voltage and amperes actually represent

Voltage (V): potential difference

Voltage is the difference in electric potential between two points. A common analogy is water pressure: it represents how strongly electricity is “pushed” through a circuit. If the voltage is too low, many devices simply will not start. If the voltage is too high, components can overheat or break down.

Ampere (A): current flow rate

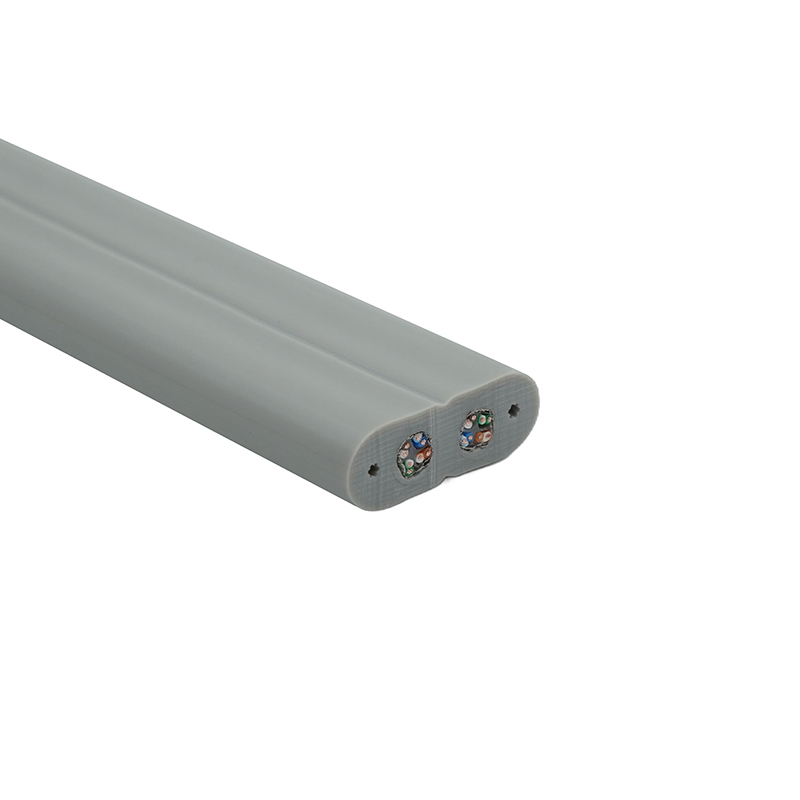

An ampere is a unit of electric current: how much charge passes a point per second. In the water analogy, amperes resemble flow rate (liters per minute). Higher current typically means more heat in wires and connectors, which is why cables, fuses, and breakers are rated in amperes.

How voltage vs ampere connect: the formulas you actually use

Three relationships cover most real-life decisions:

- Power: P (W) = V × A

- Current from power: A = P ÷ V

- Voltage from power and current: V = P ÷ A

For resistive loads (heaters, incandescent lamps), Ohm’s law is also useful: V = I × R. It explains why changing voltage changes current dramatically for the same resistance.

Practical examples with numbers

Example 1: phone charger (why higher amps is usually OK)

A typical phone might charge at 5 V and draw up to 2 A under fast charging (about 10 W). If you use a 5 V charger rated for 3 A, it does not “force” 3 A into the phone; it simply has the capacity to provide up to 3 A. The phone negotiates/draws what it needs, assuming standards and compatibility.

Example 2: a 60 W laptop adapter (current depends on voltage)

If an adapter outputs 20 V at 60 W, the current is A = 60 ÷ 20 = 3 A. If you tried to deliver the same 60 W at 12 V, the current would rise to 60 ÷ 12 = 5 A. Lower voltage requires higher amperes for the same power, which usually demands thicker cables and better connectors.

Example 3: household appliance on 230 V vs 120 V

Consider a 1500 W kettle. At 230 V, current is 1500 ÷ 230 ≈ 6.5 A. At 120 V, current is 1500 ÷ 120 = 12.5 A. The higher current at lower voltage increases heating in wiring (I²R losses) and affects circuit breaker sizing.

Quick comparison table: voltage vs ampere in real decisions

| Item | Voltage (V) | Ampere (A) | What to do |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matching a power adapter | Must match (e.g., 19 V device needs ~19 V) | Adapter rating should be ≥ device draw | Choose correct V; ensure A rating is sufficient |

| Cable/wire heating | Indirect effect | Primary driver (higher A → more I²R heat) | Size wire gauge to current and length |

| Fuses/breakers | Must be rated for system voltage | Trip rating based on amperes | Select A rating for protection; verify V rating |

| Battery capacity vs output | Battery “system” voltage (e.g., 12 V) | Load current varies with power demand | Estimate runtime from Wh, not only Ah |

Common mistakes when comparing voltage vs ampere

- Assuming a “higher amp” charger pushes extra current into a device. In most regulated electronics, the device draws the current it needs at the specified voltage.

- Ignoring power: comparing only volts or only amps without calculating watts (V × A).

- Using the correct voltage but the wrong connector polarity on DC devices. A correct “V” label does not prevent reverse polarity damage if the plug wiring differs.

- Underestimating cable losses at high current: long runs at low voltage can cause significant voltage drop, resulting in poor performance or overheating.

How to choose the right power supply using voltage and amperes

Use this checklist to avoid damage and nuisance shutdowns:

- Match the output voltage to the device requirement (AC vs DC matters; so does “regulated” vs “unregulated” for some adapters).

- Ensure the supply’s current rating is at least the device’s maximum draw (e.g., device needs 2 A → choose 2 A or higher).

- Confirm connector type, polarity (for DC), and any negotiation standard (USB-C PD, Quick Charge, etc.) if relevant.

- Check power headroom: if the device is 48 W, a 60 W supply typically runs cooler and more reliably than a 45–50 W unit.

- For long cables or high current, account for voltage drop; consider thicker gauge or higher system voltage when feasible.

Safety perspective: which matters more, voltage or ampere?

Safety depends on the scenario:

- For electric shock, voltage is the main enabler because it drives current through the body. However, harm is fundamentally caused by current through tissue, which varies by conditions (skin resistance, contact area, environment).

- For overheating and fire risk in wiring and connectors, current (ampere) is usually the key factor, because heating scales roughly with I² (current squared) in resistive elements.

The practical takeaway is straightforward: match voltage to the device, and size amperes for the wiring and protection.

Conclusion: how to think about voltage vs ampere

Voltage is the required level; amperes are the required capacity. If you remember one rule for everyday choices: use the correct voltage, and ensure the available amperes are equal to or greater than what the device needs. Then validate connector/polarity and confirm power (watts) so the system operates reliably and safely.

EN

EN

English

English русский

русский Español

Español